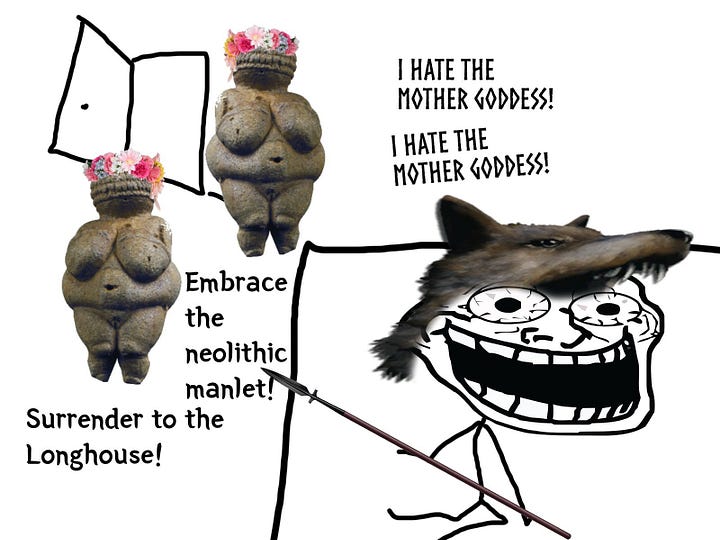

Amidst a landscape of cultural discourse that increasingly favours “gender warfare”, a peculiar and funny meme has emerged: that of the “longhouse”. This whimsical reference alludes to the idea that matriarchal, egalitarian cultures are bastions of emasculation and the metaphorical longhouse is where masculinity languishes under the jackboot of feminine dominance. Like all successful memes, it belies something of a deeper truth, but perhaps not the one many would suspect. Among more conservative types, and even among many students of Traditionalism, one finds persistent support for the idea of a patriarchy and an entrenched and rather simplistic belief that men as a broad category are entitled to authority over women simply by virtue of being male, regardless of whether or not those males actually embody the masculine principle that is at the root of patriarchal authority. From a Traditionalist perspective, the reality is more complex. While Traditionalism recognises patriarchy as an ideal, it is not an ideal that exists in a vacuum but rather one that is downstream from a specific human type. Given the popularity of this meme, I thought it worthwhile to attempt to place the concept of matriarchies and the circumstances under which they develop in a proper Traditionalist context.

Matriarchies arise when the men in society are only an expression of phallic man. Phallic man is a truly Hobbesian character, overcome by his base, animal urges and his cravings for material satisfaction. His primary purpose in life is to seek to fulfil his desires (desire being the fundamental essence of the feminine). Once he has obtained what he wants, he fears to lose it and experiences anxiety if he is deprived of it. No matter how many of his desires he fulfils, new ones crop up to take their place, the fulfilment of each desire only leading to more craving. He is profoundly attached to materiality, which, as we know, is the realm of Becoming and under the aegis of the feminine. Phallic man resides in the sublunary sphere, under the veil of illusory Maya, and he believes it is real. As a result, phallic man is cut off from the transcendent. He may look like a man, but in truth, he is little more than a talking, intelligent animal.

By contrast, patriarchies are meant only for societies made up of heroic men. Heroic man is the opposite of phallic man. He has broken the chains of desire. He is a master of himself— of his desires, cravings, temptations, of his baser nature. He is equanimous and detached, an embodiment of the calm centre in the eye of a storm. He is neither in a state of desire nor fear. Whether something is given or taken away, he is not perturbed. Heroic man has broken free of illusion, he has recognised that it is not real. He has become spiritually liberated. In doing so, he has activated an inner masculine virility within himself, thereby becoming stronger than the feminine. Where the feminine once had authority over him, he now has authority over the feminine, having transcended its bonds. When man has mastered the feminine in himself, he naturally also becomes the master of women and men who behave like women.

As such, patriarchy is a reflection of heroic man’s mastery over the feminine realm of Becoming. Only the man who has been in touch with a state of Being is qualified to impose a solar order on the world and other people. He must first have that sense of order in himself. Phallic man cannot do this because he has no conception of what order means, in the cosmic sense. For phallic man, patriarchy simply means that he would acquire the power to better satisfy his material desires or to create structures for himself that protect him from any challenges that would demand real masculinity. Heroic man has both the wisdom and disposition to be a good steward of those under his authority. His non-attachment to materiality allows him to be fair, impartial, and just. His innate virility allows him to confidently meet and overcome challenges. Phallic man can only ever be self-serving and cowardly, as his cravings and aversions ultimately have more control over him than he has over them. The pull of his desires make him prone to corruption.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to PhilosophiCat’s Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.