Julius Evola begins this chapter with a consideration of a mythological reference point for understanding the metaphysics of sex: the myth of the hermaphrodite. He says that myths have the value of a key, and indeed in the traditional world, myth was how profound truths about the nature of ultimate reality were conveyed. For this chapter, Evola relies heavily on Plato, particularly the Symposium. He says that all of the myths that Plato introduces in his philosophies stem from the initiatic ceremonies of the ancient Greek mysteries, but that this theme is also found in various other traditions.

Plato reports that the hermaphroditic race was a primordial race whose “essence” is now extinct. They contained both the male and female principles within them and were said to be extraordinarily strong and brave. They were also prideful and arrogant, having made an attempt to scale the skies so that they might challenge the gods. In retribution, the gods paralysed their power by splitting them into two: males and females. But these new single-sex beings retained a memory of their earlier state and this gave rise to an impulse to reconstitute that primordial unity. It is in this impulse that the ultimate metaphysical meaning and ultimate goal of eros can be understood: two halves seeking to recreate the whole.

We find also this theme of hubris repeated in many other myths, from the Titans to the Giants to Prometheus. We find it in the Grail legends, in Vedic mythology, in the biblical myth of Adam and Eve, and more. In The Hermetic Tradition, Evola notes that there are two categories of myths that deal with this theme. One category features a hero who successfully makes the “Olympian leap” and succeeds in proving himself worthy of the gods. The second features a failed attempt in which the would-be hero is punished for his audacity and these stories tend to function as warnings against pursuing what is essentially a “left hand path” or a “wet path”.

The “Promethean” character that Plato has given the myth of the hermaphrodite is significant and Evola explains why:

“If the mythical beings of the earliest times were such that they could strike terror in the gods and vie with them, then we can hypothesise that eros—the ultimate search for integration—is not so much a nebulous mystic state as a condition of being that is also potency.”

That is to say, there is real power to be found in the union of the male and female, a power that is sufficient to garner the attention of the gods, and this will be important for the later discussion regarding initiatic forms of sexual magic. This is a path of “immortality” and “everlasting life”, a reward that belongs only to those who pursue the “Tree of Life” at any cost, and this is attested to across many traditions, including medieval Grail cycle, which contains initiatic content encoded within the chivalric tales. In the legends of the Grail, the path of love is a dangerous one. The ultimate reward lies at the end of that path, but it is like walking the razor’s edge where one false step can be a fatal cut. (See The Making of a Hero for more on this.)

In any case, the myth of the hermaphrodite emphasises a change from unity to duality, from a state of Being to a state cut off from Being and from “everlasting life.” This is the importance of the myth. Evola writes:

“Here is the key to all the metaphysics of sex: ‘Through the Dyad toward the Unity.’ Sexual love is the most universal form of man’s obscure search to eliminate duality for a short while, to existentially overcome the boundary between ego and not-ego, between self and not-self.”

According to Plato, the return to the primordial condition and the “supreme happiness” (which is the highest “good” to which eros can lead) are associated with overcoming godlessness, which is the chief cause of man’s separation from the divine. The implication here is that there is something fundamental about the restoration of the unity of the male and female as a pre-requisite to any new Golden Age.

Another myth that Evola draws on is the myth of Poros and Penia, also found in Plato’s Symposium, which Evola says contains a profound significance. In this story, Poros, representing the masculine principle, had attended a banquet in the garden of Zeus to celebrate the birth of Aphrodite. Penia, representing the feminine principle, had come to beg at the threshold of the garden. Poros became drunk and sleepy and Penia took advantage of his inebriated state, with the intent to conceive a son by him. That son was none other than Eros.

Poros here expresses a state of fullness and Being, but he has fallen into a stupor, as man has fallen under the illusory and intoxicating veil of Maya. Penia is expressing a state of privation, of neediness. She has no Being of her own and seeks to obtain it from Poros. This is a profound statement on the nature of man and woman. The feminine principle on her own has no Being, no form. It is only pure, un-actualised potential. Any possibility for actualisation (and therefore manifestation) must come from the masculine principle. The masculine principle is self-sufficient, but forgets his own nature when pulled under the veil of illusion, which is to say, when he becomes embodied in and participates in materiality. He not only becomes subjected to the law of duality, but actually generates it. A similar theme is echoed in the myth of Narcissus who falls in love with his own reflection in the water (water being a prominent symbol of the feminine principle) and thereby drowns in it. The masculine principle, upon seeing himself reflected in the feminine principle, “swoons” and the two principles unite, giving birth to the cosmos.

What the myth of Poros and Penia is speaking to, though, is not the love born of a mutual desire between two people who are in love with each other and see themselves reflected in the other, but of a lower form of desire that is born from a lack of reason (Poros is the son of Metis, “wisdom”, and it is significant that he is represented in a debilitated state far removed from his proper nature) and from a state of eternal craving. Evola writes:

“The Greek philosophers saw, as the substance and sense of the génesis (creation) of existence enclosed in the everlasting circle of generation, the state of ‘that which is and is not,’ a ‘life mingled with non-life’; and non-life is the nature of love and desire revealed to us by the myth of Poros and Penia. Lovers, inheriting the intoxication that overcame Poros when Aphrodite was born, are actually giving themselves to death when they believe they are continuing life by desiring and procreating. They think they are overcoming duality, when in fact they are reconfirming it.” (P59)

The emphasis Evola gives to the state of privation and craving is important to understand. He makes a clear delineation in this book between lower, profane forms of sex that are focused on the sensual and physical procreation versus higher, sacred forms that treat sex as a vehicle for what is essentially a “Great Work” and a ritual recreation of the primordial act, in which physical procreation is counter-indicated and often actively avoided.

In fact, Evola discusses different types of “mania”, and in particular erotic mania. This is not the mania that arises from human psychological defects, but from a divine exaltation, and great benefits may come from this type of erotic mania, which was seen as a blessing from the gods. However, when this mania deteriorates and carnal craving is introduced, it leaves the supersensual plane and enters the lower realm of biological determinism. There are two pathways by which this deterioration can go. One is the impulse of eros being directed toward the cycle of physical procreation and away from absolute Being. As eros becomes a more and more extraverted desire, its true purpose is actually obscured behind the procreative narrative: to seek out a substitute for the metaphysical confirmation of Self. And as the desire becomes increasingly outwardly focused, it becomes carnal lust and eros collapses into a purely animal sexual instinct.

Evola is careful to separate erotic love from a Platonic “love of beauty” and says that while a love of abstract and pure beauty may have a place in metaphysics, it does not relate to the metaphysics of sex. The love of and desire for abstract beauty is not driven by the “magnetic fluid” that woman and man arouse in each other. In fact, not only is a love of idealised beauty not the same as erotic love, but they are opposites of each other. Idealised, abstract beauty tends to inspire reverence and awe, rather than lust. It tends not to arouse lust because no normal man wants to desecrate such beauty by dragging it onto the lower level of carnal desires. Evola remarks that from the point of pure beauty, the most ideally beautiful woman is therefore not the most suitable woman to arouse erotic desire, because the most ideally beautiful woman would have a beauty that is devoid of the fascinating, abyssal, daemonic quality of the raw feminine that is essential to erotic love and the magnetism of lovers. It’s a beauty that may be perfect and flawless, but it is too sterile to arouse passion. Evola notes that the women who are the most alluring are often those who cannot rightly be called beautiful in a purely aesthetic sense. Instead, their imperfections, their “realness”, are what put them in touch with the primordial úlē that their sex embodies. (See Woman as Power for more on this.)

It is sometimes said that among the Greeks, the homosexual love for epheboi was closer to the love inspired by pure beauty than that of the eros aroused by a woman. This is a question that Evola fortunately addresses in the appendix on homosexuality and he considers a number of points.

Firstly, when considering a love of divine beauty in the abstract sense, there is no real metaphysical problem if the source of the inspiration happens to be a being of the same sex, so long as it has no carnal element. Evola says that the pederasty of the Greeks may at one time had a truly noble character, but as the ancient customs declined, there is less and less evidence of anything like a pure and noble love remaining, and that homosexuality became increasingly carnal. In order for Greek pederasty to have remained in the more noble realm of a Platonic contemplation of beauty, it could not have any sexual element attached to it. Evola says that where homosexuality mimics the relations between a man and a woman, that this is a deviation from the metaphysics of sex, since it no longer permits an impulse to reunify the primordial being.

Because the metaphysics of sex cannot explain this, we must look to a lower plane of examination. Evola notes that sexology recognises two forms of homosexuality, inborn and environmentally conditioned, but he acknowledges that homosexuality is hard to explain, admitting confusion as to what could drive “a man who is truly a man” to feel sexually towards another man. He speculates that it may simply be a case of “mutual masturbation”, exploiting conditioned physical reflexes for pleasure. In the case of a homosexual union, both the physical and metaphysical premises for the “destructive union” are lacking.

One may be tempted to suggest that perhaps the explanation is that the homosexual embodies a nature that is reflective of hermaphroditic unity, but Evola swiftly dismisses with such a notion:

“As to the claim for an ideal nature of hermaphroditic wholeness in the pederast who acts both as man and as woman sexually, that is obviously fallacious beyond the level of straightforward sensations; hermaphroditic wholeness can only be ‘sufficiency,’ for it has no need of another being and is to be sought at the level of a spiritual realisation that excludes the nuances that the ‘magic of the two’ can offer in heterosexual unions.”

Because the quality of the unified being is that of sufficiency— it is no longer seeking its other half— then anyone with a truly hermaphroditic nature would have no need for an “other half,” no need for a sexual partner.

Evola concludes that “when homosexuality is not ‘natural’ or else cannot be explained in terms of incomplete forms of sexual development, it must have the character of a deviation, a vice, or a perversion.” He goes on to say that in cases of extreme erotic intensity between homosexuals, this can be explained by a displacement of eros, and he notes several other examples of bizarre targets of eros, from unusual fetishes to bestiality to necrophilia. That homosexuality is a more common displacement of eros does not disqualify it from being categorised with the others. A being of the same sex is then functioning simply a psychic support for physical arousal with no profound dimension or higher meaning whatsoever. Even in cases of certain peculiar practices of heterosexual sex, such as sadism, it is still possible to find some elements that are incorporated with a proper metaphysical framework and which only turn into perversions when taken outside of certain limitations, but Evola says that not even this can be said in the case of homosexuality.

There are a couple of foundational points we can take away from this chapter as regards the metaphysics of sex. One is the idea that there is a lost unity that we seek to restore and that eros is the force that drives humans towards this reintegration, where the sexual act is simultaneously a microcosmic and macrocosmos act that is aimed at overcoming the separation. The other is that the nature of eros itself is related to the tension between the masculine and feminine principles, and the union of these two principles holds the potential for higher Being (provided that the union transcends the lower cravings of biological determinism). The dichotomy of the sacred versus the profane is a significant theme in this book, but while sacred uses of eros can operate as a vehicle for spiritual transformation through the transmutation of sexual energy towards ends higher than the merely physical, profane experiences of eros can sometimes offer glimpses of transcendence, and it is the profane sphere of experiences on which the next chapter will focus.

Link to Chapter One

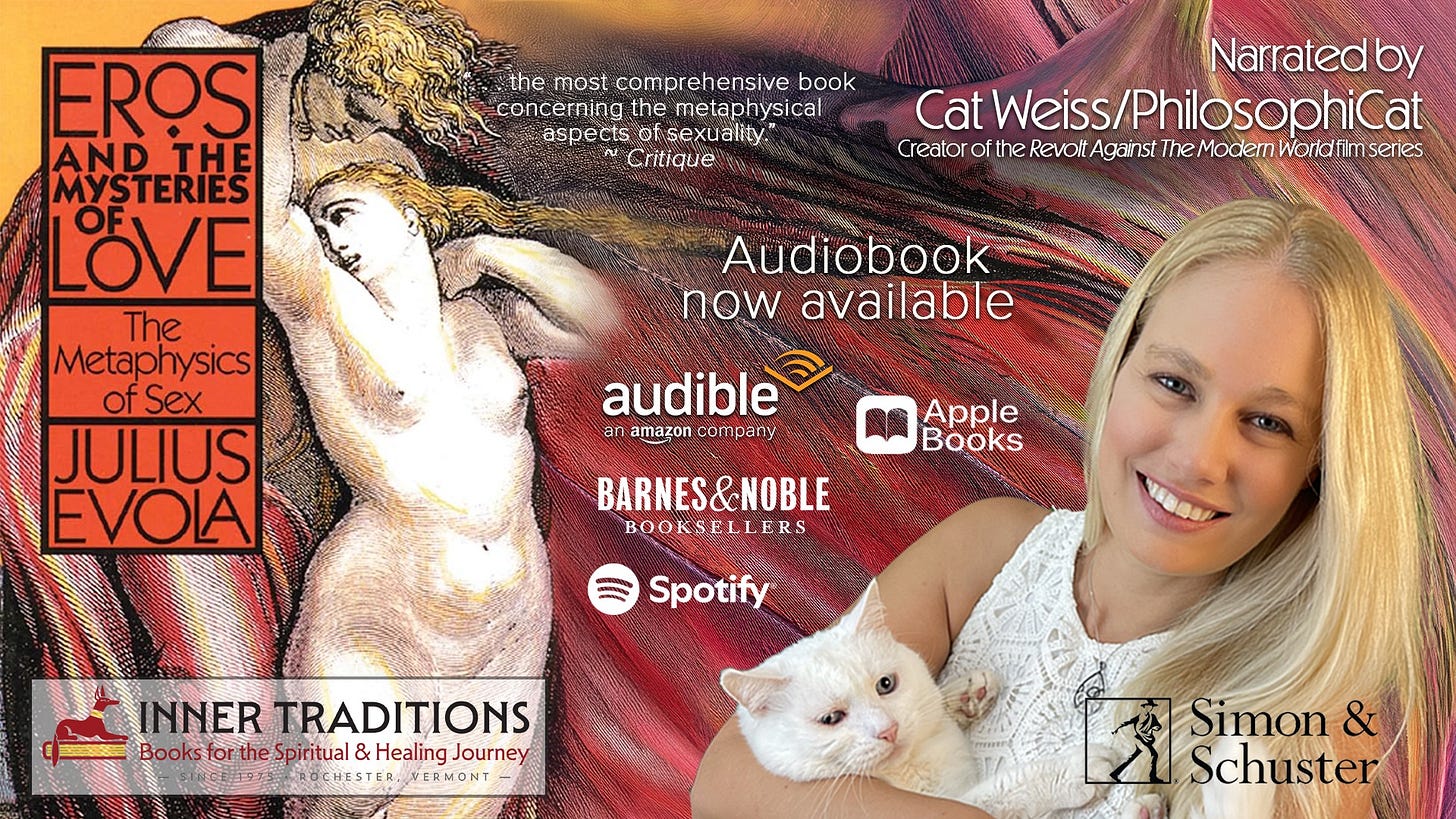

This article is part of a series intended to introduce the reader to Julius Evola’s book, “Eros and the Mysteries of Love”, which is now available in audiobook format, narrated by me. Please consider purchasing the book and using these articles to help guide your study.

An exciting read. This has opened up a great deal of which I hadn't even considered.

I'm hoping these chapters might help me.

Thanks PhilosophiCat.